Seasteading tech for ten thousand startup countries our best chance for liberty

The Seasteads are Here

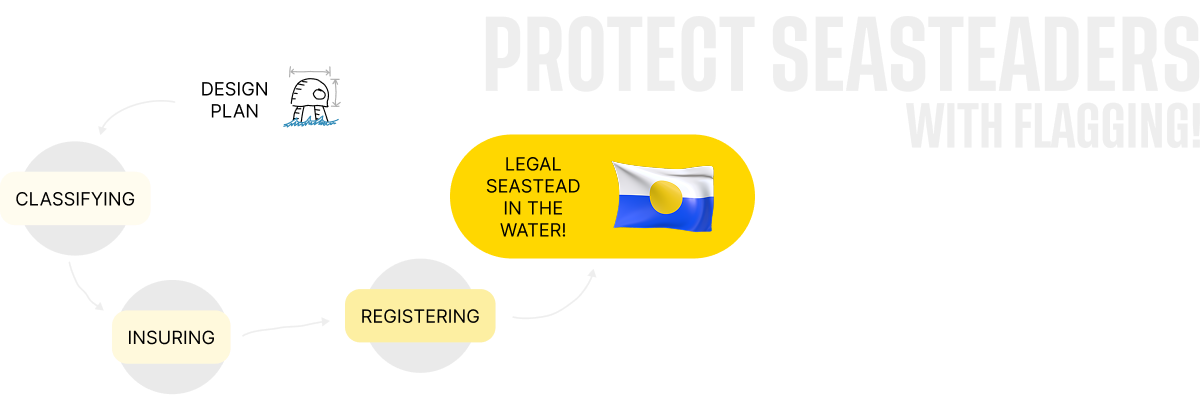

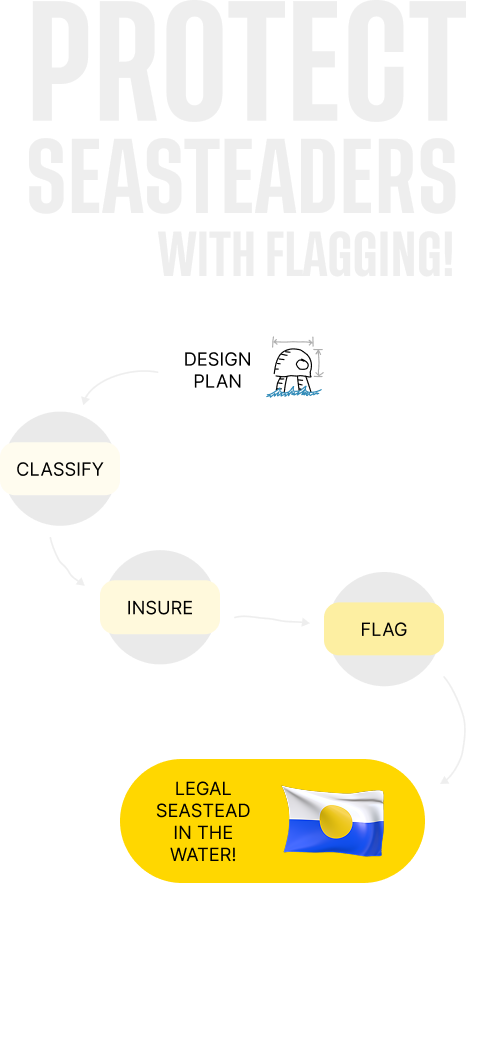

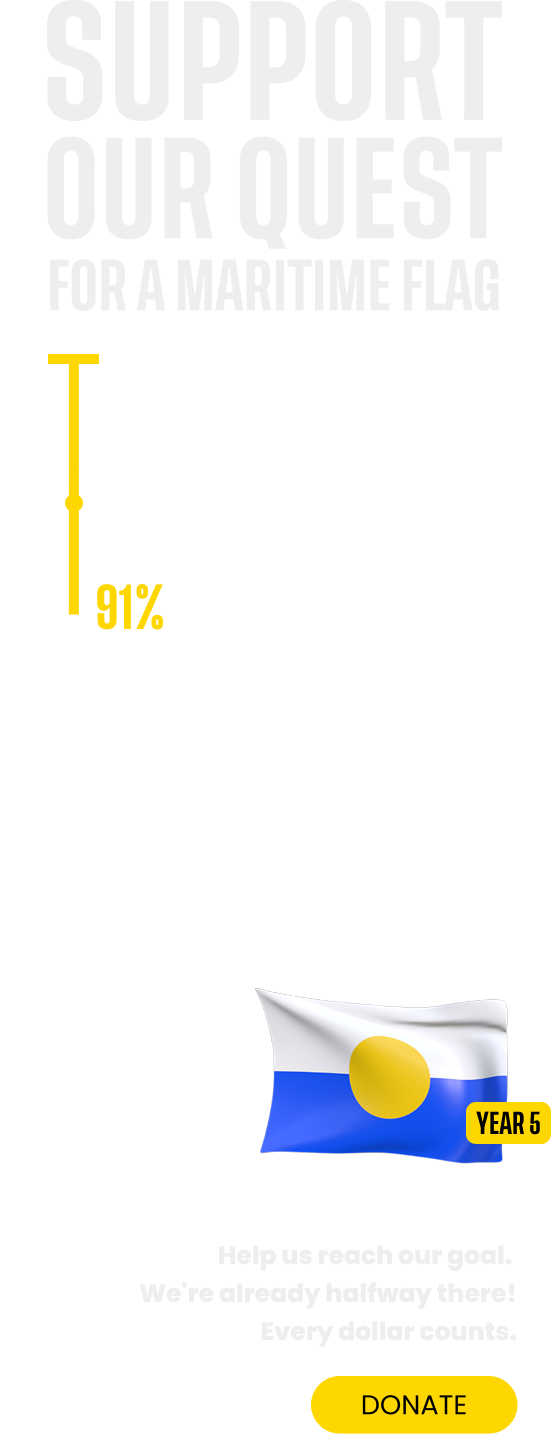

Learn about the revolutionary technology for eco-restorative ocean communities and our plan to secure political autonomy for all seasteaders.

The Seasteading Institute is a nonprofit organization.